In the summer of 2019, Jaleel Huggins-Cotton laid eyes on his father for the first time since he was six months old.

It was Jaleel’s mother’s birthday and, on a whim, Takeya Huggins Cotton Tilghman took her son to the old neighborhood in West Philadelphia to see if the absent side of his family might still be around.

Jaleel’s grandmother was on her front porch that day and an uncle offered to call Jaleel’s father, who lived around the corner. While waiting, Jaleel channeled nervous energy into fixing his clothes and brushing his hair.

When Jaleel stood face to face with his father, Tony Montgomery, who had been locked up in federal prison for most of Jaleel’s life, he noticed the same light muscular build, posture and eyebrows.

Jaleel remained cool, yet “it was a ‘where you been all my life?’ moment,” Takeya recalled.

The family got reacquainted over a macaroni and cheese dinner that lasted until 2 a.m. After that night, Jaleel and his father talked on the phone constantly, Takeya remembered, and Jaleel was excited to forge a new relationship unburdened by resentment.

Six months later, Jaleel was denied that second chance when Tony died of a heart attack. Jaleel could not take off work to attend the funeral.

Eight months later, on August 7, 2020, Jaleel was fatally shot while waiting outside of a store on the 1500 block of South 52nd Street in Southwest Philadelphia. No arrests have been made, but the family believes that Jaleel was the intended target. A surveillance video shows a person with an oversized blue-and-white umbrella obscuring Jaleel before he is shot by someone else from behind, Takeya said.

Jaleel left his son, Kamai, now 3, and daughter, Khloe, who is almost 2, fatherless.

“He liked being a father and wanted to be a father because he never really had a father in his life,” Takeya said.

“He wanted to get his life together to give his kids the life he never had,” added Jaleel’s cousin, Shanece Cotton.

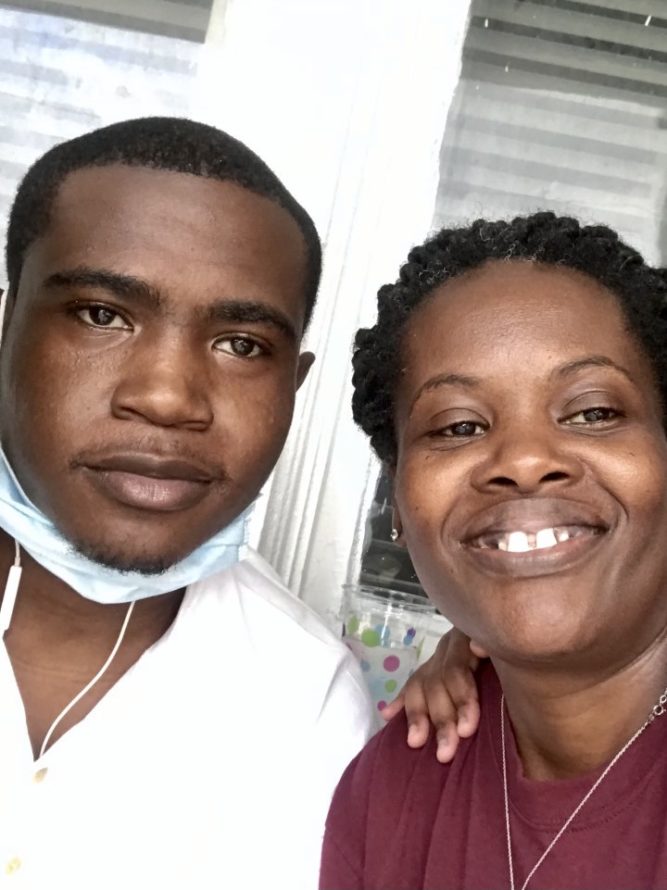

Jaleel and his cousin Shanece Cotton

Born and raised in Dover, Delaware, young Jaleel relished family time with Shanece and their grandmother, Marjorie Cotton.

While sharing a household, Shanece and Jaleel could be mistaken for brother and sister. They both played drums in the Academy of Dover Charter School marching band.

Marjorie happily cooked Jaleel (or “Jaloody,” as she affectionately called him) four-course breakfasts. Jaleel was a Halloween baby, and his grandmother would make him his favorite shrimp Alfredo before sending the children off to trick-or-treat for dessert.

Soon, Jaleel followed Marjorie into the kitchen to experiment (“If you want to eat, you gotta learn how to cook it,” she quipped.) Although Jaleel prized cleanliness, it was one of the few times that he was fine with getting his hands dirty.

“They had an awesome relationship. It was like I was the carrier and she was the mom,” Takeya remembered, laughing.

When he was five years old, Jaleel accompanied his grandmother to her dialysis appointment, Takeya said.

“Why is it called dialysis,” Jaleel quizzed the doctor. “It should be called live-alysis.”

He repeatedly offered to donate a kidney to his grandmother, but she refused. The two were tight and Marjorie supported Jaleel unconditionally, including his goal of becoming a professional football star.

Naturally talented, Jaleel enjoyed the aggressiveness of the game and the brotherhood. “The girls were the bonus,” Takeya said.

Jaleel won trophies in the Pop Warner youth football program and, in high school, he became varsity quarterback for the Caesar Rodney Riders.

Jaleel and his family

Although he dropped out of school, Jaleel took summer classes and eventually graduated in 2017, shortly before his son was born.

Unfortunately, his grandmother Marjorie was not in the stands. She died in 2013 from sepsis — two days before Jaleel’s birthday.

As the family grew more fractured, Jaleel’s grief became more pronounced.

When Jaleel wanted to talk about something serious, Takeya remembered, he lay down and she sang “You Are My Sunshine,” rubbing his nose. It was the same song that he heard on repeat in the womb.

On the outside, Jaleel was a fun-loving social butterfly, who clowned around like his favorite comedian, Kevin Hart, and wrote rap lyrics that flowed like poetry, Takeya said.

When Jaleel’s sister Jah-mya, was born a decade ago, he yearned for a boy. He christened her “James,” and she answered to it.

“I’m just gonna beat her up like a boy,” he teased.

“He loved being the center of attention,” Shanece recalled. “He just enjoyed seeing other people laugh because of his silliness.”

Jaleel worked odd jobs at McDonald’s, Target, a Perdue plant, and DoorDash, but it was always football or bust. His backup plan was to join the Navy, yet he became discouraged after failing the entrance exam, his mother said.

Takeya coached her son before job interviews: Look the person in the eye, be honest, don’t chew gum, don’t twiddle your fingers, ask questions.

But he kept getting passed over. And he had too much down time.

“I always told him your life is going to catch up with you,” Takeya said.

Her son tried to ease her fears: “I’d rather be dead than in jail.”

In April of 2020, Jaleel and Takeya moved from Delaware to West Philadelphia. Jaleel enjoyed the vibrancy of city life, but he was nursing a breakup that disrupted his relationship with his children.

“I wish my grandmother was right here next to me,” he wrote on Facebook at the time.

Although Jaleel struggled financially, he believed in helping the most vulnerable.

“Match me,” he would challenge Takeya, before handing a homeless person a dollar.

“God looks at the fact that you’re helping other people,” he explained. “They are worse off than you. That’s your blessing.”

On the day he died, Jaleel dropped off a pack of cigarettes for his mother. Then he rushed out the door before she could thank him.

At 8:05 p.m. on Aug. 7, 2020, Takeya texted her son: “I love you” (kissing face emoji)

“Love you too” (kissing face emoji with hearts).

Less than an hour later, Takeya heard police sirens as if they were screaming Jaleel’s name.

“You good, son?” she texted at 9:43 p.m. “Hello?”

At 8:44 p.m., police found Jaleel lying on the street, suffering from multiple gunshot wounds. He died that night at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center.

He is buried in Friends Southwestern Burial Ground in Upper Darby. Jaleel became a devoted Muslim later in life, and mourners recited the Janazah (an Islamic funeral prayer).

When she came upon the open casket, Takeya rubbed her son’s nose, gently.

Resources are available for people and communities that have endured gun violence in Philadelphia. Click here for more information.

A reward of up to $20,000 is available to anyone that comes forward with information that leads to the arrest and conviction of the persons responsible for Jaleel’s murder. Anonymous calls can be submitted by calling the Citizens Crime Commission at 215-546-TIPS or the Philadelphia Homicide Unit at 215-686-3334.

Leave a Reply